Japanese Americans’ pain over their mass incarceration has been minimized. New essays let them speak

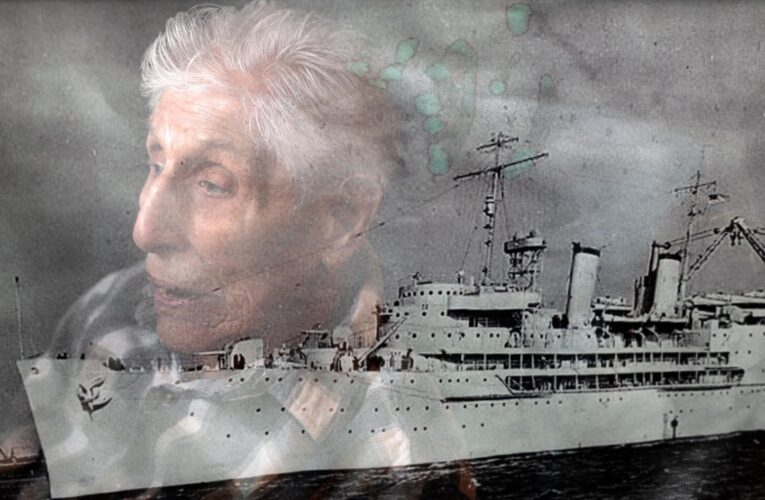

Book review The Afterlife Is Letting Go By Brandon ShimodaCity Lights Books: 232 pages, $17.95 If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores. During World War II, Fred Korematsu, one of the 120,000 Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans incarcerated under President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066, refused to be moved into horse stalls and was convicted for resisting. The American Civil Liberties Union challenged his conviction, but the Supreme Court ruled against him, citing military necessity. Forty years on, however, a federal district court vacated the conviction, because the Department of Justice had originally withheld evidence showing there was no military necessity. Korematsu received a Presidential Medal of Freedom. Reparations were paid to him and others of Japanese ancestry. But the legacy of those imprisonments is pivotal for many Japanese Americans. Fourth-generation Japanese American poet Brandon Shimoda’s “The Afterlife Is Letting Go,” a well-researched, intriguing essay collection, reappraises not only the official narratives but also the supposedly ameliorative efforts made subsequently. (City Lights Books) In 15 essays, Shimoda blends interviews and